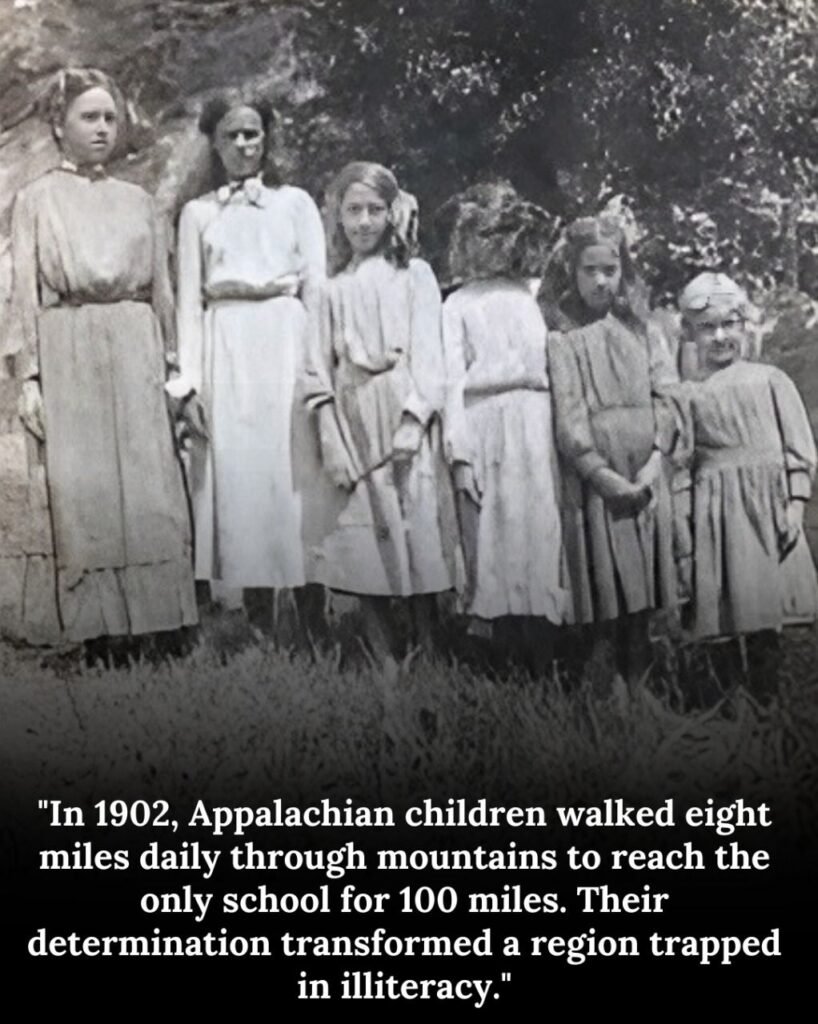

In 1902, eastern Kentucky was beautiful and brutal—mountains so steep that isolation wasn’t a choice, it was geography.

Most children in Appalachia couldn’t read. Most couldn’t sign their names. Not because they lacked intelligence, but because there were no schools. No teachers. No books. Families lived scattered across remote hollows, miles from the nearest neighbor, trapped by terrain that made education physically impossible.

Illiteracy wasn’t a personal failure. It was a structural reality.

Then two women decided to change that.

May Stone and Katherine Pettit were educated, privileged women from Kentucky’s cities who could have lived comfortable lives. Instead, they rode horses into the most isolated corners of Appalachia, saw children with brilliant minds and zero opportunities, and founded the Hindman Settlement School in 1902.

It was the first settlement school in the southern mountains—a radical experiment in bringing education to people who’d been abandoned by every system.

The school taught reading, writing, mathematics, agriculture, carpentry, and sewing. But more than that, it taught possibility. It told children trapped by geography that their lives could be different.

Word spread slowly through the mountains. Families who’d never imagined their children attending school began to reconsider. But the logistics were devastating: children lived four, five, sometimes eight miles from Hindman over mountain terrain with no roads, no transportation, just narrow trails through forests and across creeks.

Most families assumed it was impossible. The distance was too far. The children were needed for farm work. What was the point?

But some children went anyway.

Stories—some documented, some passed down through oral tradition—tell of siblings walking together before dawn, covering four miles of mountain trails to reach school, then walking four miles back after classes ended. Eight miles daily. Through mud that sucked boots off feet. Through snow that made trails disappear. Through summer heat that left them dehydrated and exhausted.

They carried no lunches—there was no food to spare. They wore patched dresses and worn boots held together with wire. They walked with blistered feet and empty stomachs.

But they carried something more valuable than food: determination.

These weren’t isolated incidents. Across Appalachia, once Hindman proved education was possible, children began walking extraordinary distances to attend school. Some walked alone. Some walked in groups. Some were as young as six years old, holding their older siblings’ hands on treacherous paths.

Their journey became more than transportation. It was defiance against a system that had written them off. Every step said: We refuse to be defined by where we were born.

Other families noticed. If those children can walk eight miles daily, maybe mine can walk six. Maybe mine can walk four. Enrollment grew. Other settlement schools opened across Appalachia, inspired by Hindman’s model.

The impact was generational. Children who learned to read taught their parents. Literate adults could read contracts, understand legal documents, advocate for themselves. Communities that had been exploited by coal companies suddenly had tools to fight back.

Education didn’t just change individual lives—it transformed the power structure of an entire region.

Hindman Settlement School still operates today, 122 years later. It’s now a cultural center preserving Appalachian heritage while continuing educational programs. The original mission—bringing learning and hope to isolated mountain communities—remains unchanged.

The specific “six sisters” may be a representative story rather than documented individuals, but the reality they represent is verified: countless Appalachian children walked extreme distances to access education in the early 1900s. Their determination built a movement.

Those children grew up to become teachers, farmers, business owners, activists. They raised children who attended college. They built libraries and schools in communities that had none. They proved that poverty and geography don’t define potential—they only limit access.

And access can be fought for.

Today, we complain about school bus routes and drop-off times. We debate whether children should walk three blocks unsupervised. We’ve forgotten what determination looks like when the alternative is a lifetime of illiteracy and exploitation.

Those Appalachian children walked eight miles daily—often barefoot, always hungry—because they understood something fundamental: education is the only inheritance that can’t be stolen.

In 1902, May Stone and Katherine Pettit opened the first settlement school in Appalachia’s most isolated mountains. Children walked up to eight miles daily—through mud, snow, and hunger—to attend.

They had patched dresses, blistered feet, and empty stomachs. But they had determination.

Their walks transformed a region trapped in illiteracy and exploitation into communities that could read, write, and fight back.

Hindman Settlement School still stands today, 122 years later.

Those children’s footsteps echo—reminding us that education isn’t given. It’s fought for.

Eight miles. Every day. Through mountains.

That’s not just a walk to school.

That’s revolution in worn boots.